How do you teach students to be media savvy citizens, ready to understand the complex dynamics of the modern political landscape? By making them run for office, of course.

Every year since Cary Academy first opened its doors, eighth-graders have participated in a mock election. “It seems like, if you’re trying to introduce American history and government, the logical starting point is to show how it all works, beginning with the electoral process,” explains eighth-grade history teacher David Snively.

ALL POLITICS ARE LOCAL

To be clear, this isn’t your typical mock election, nor is it a costume contest. Students are challenged to take on a role that represents the various dimensions of our electoral process: candidate, campaign staff, or journalist. Most importantly: everyone is a voter. Everyone.

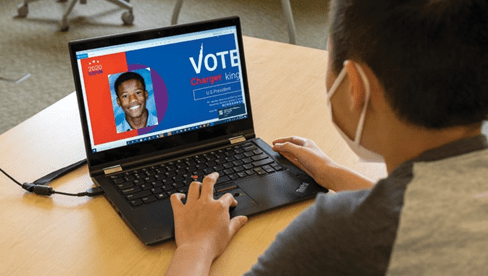

Candidates who seek office in the United Regions of Cary Academy (URCA) construct personas, build biographies, and decide key issues around which they build their platform and recruit campaign staff. Members of the campaign teams do everything from researching the issues and drafting campaign speeches and position papers, to fleshing out the platform and engaging the public, to devising advertising strategies and courting donors—more on that in a bit—all to give their man (or woman) the edge. Journalists investigate the candidates and the issues that matter to the voting public while producing news and opinion pieces for the primary media outlet of the URCA, The Cary Communicator, under the auspices of Editor- in-Chief (and eighth-grade language arts and history teacher) Meredith Stewart.

As in a real election, laws and regulations are enforced by an oversight body—in this case, the Board of Elections (aka Snively and Stewart). The “B of E,” as it’s affectionately known, doles out public financing, sets rates for media advertisements (curiously unaffected by inflation since 1997), manages voter registration, levies fines, approves materials distributed to voters, manages the candidate debates, and conducts the election day vote.

VOTING REFORM

In a typical year, every citizen of the United Regions of Cary Academy is provided $50 (CAD—Cary Academy Dollars) to back the candidate(s) of their choosing. Those publicly-sourced funds are the lifeblood for the campaigns and their only way of buying airtime and ad space to get their message out to the electorate. Candidates and campaigns vie for the voting public’s votes and financial support through advertising, candidate forums, statements to the media, and public appearances that give candidates and their staff the opportunity to press the flesh (at a distance this year), answer questions, and persuade the undecided.

However (here it comes), in the URCA, as in real life, election 2020 was anything but normal—but that doesn’t mean it didn’t reflect the real world. With the school year starting with remote learning, the highly collaborative nature of the election project convinced Snively and Stewart to push back the assignment until after Cary Academy resumed in-person learning.

“Despite everything going on, because it is an election year, we could not not do this. But we couldn’t carry on as usual, either,” says Snively. “We had to rethink how we run the project, to adapt to having only some students in-person each day, and some students who are always virtual.”

So, in-person fundraisers and candidate meet-and-greets were out, and public financing of the campaigns was in. Each candidate received a set amount of funding upon which to draw, regardless of their number of supporters.

2020 also saw another change to how the United Regions of Cary Academy votes. (Heck, even the URCA itself changed, into the more recognizably-named “United States.”) Rather than one election, with everyone a member of the electorate, Gold cohort candidates court Blue cohort voters and vice-versa. This means personal (and political) allegiances were less likely to impact votes, and playing roles on both ends of the election provided the opportunity for students to engage the process from multiple perspectives, making them a little more media savvy in the process.

Because the Middle School is not host to the electoral trenches of a more typical campaign season, one other change

has come to the eighth grade’s election project. The eighth grade was asked to put together brief live Zoom presentations with visual aids to demonstrate their understanding of elections and help educate their sixth and seventh-grade peers, who won’t get to witness the

eighth-grade election in-action.

ELECTORAL COLLEGE COUNSELING

You’re probably wondering: how does this translate into students better understanding how real elections work and increased civic engagement when

they reach voting age? It all boils down to simulating reality.

“You’d be surprised to know that— despite this being a class project that takes place during the school day—just like in the real world, not everyone registers to vote,” laments Snively. “Each year, about a dozen students fail to register. Of those, three or four will show up to vote and get turned away.”

The United Regions of Cary Academy doesn’t use a convoluted system

to register voters—well, no more convoluted than the real world—it uses North Carolina’s voter registration forms (with “NC” carefully scratched out and “CA” carefully written in). Only, instead of submitting them to the county board of elections, the forms go to the good ol’ B of E. Just like in the real world, errors on the forms result in voters being omitted from the rolls. This critical lesson is much easier to swallow for students, than learning it the hard way on your first election day.

Much like the real world, URCA citizens are required to vote on their own time on election day—there’s no time off from class to vote, and if you don’t get to the polls before they close, you’ve missed your chance to have your voice heard.

According to Snively, this fact surprises some students; he notes that at least five or six students forget to vote each year.

Votes cast do not count towards the direct election of candidates. Like the United States of America, the United Regions of Cary Academy relies on an electoral college system. Students are assigned regions, and those regions are awarded electors based on populations.

In the past, some campaigns have used this to their advantage, recruiting staff from highly-populated regions to capture their all-important electoral college votes (for example, hiring three staffers from a region might almost guarantee winning that region’s electoral college votes). That strategy won’t work in 2020, with the divided, cohort-based electorates.

The project has even proven eerily similar to real life. One year, a spate of inconclusively marked ballots and a very, very tight margin of victory led to a particularly memorable election. The Supreme Court of Teachers was convened to rule on whether or not voters’ intent could be determined by the Board of Elections when ballots were subjectively marked. Sound familiar?

But not everything reflects the real world. In the URCA, there are no primaries (election season is simply too brief), and candidates’ statements, platforms, and advertising—as well as journalists’ reports—are held to the CA Statement of Community values. “No matter how outsized some of the

personalities they construct might be, we still have to live in the same community at the end of the day and the end of the election,” explains Snively.

THE RESULTS ARE IN

To be clear, these aren’t trivial campaigns about what’s on the menu in the dining hall or which clubs should be offered next trimester. Instead, students tackle real-world issues, including tax rates, environmental policy, healthcare, and the minimum wage, to name a few.

Historically, members of the 8th- grade electorate form non-partisan political organizations around issues that are important to them. Analogous to Political Action Committees, these groups not only tend to sway the political conversation but extend the project’s impact beyond the conclusion of the URCA election season.

“Many times, students choose to focus their persuasive letter project—which happens during the second trimester—on issues they became passionate about during the election project. Often, these are subjects they knew nothing about before researching it for a campaign or a journalistic article,” says Stewart. These conversations extend outside of the classroom, too. Snively often observes students discussing healthcare policy during lunch, and many eighth-grade parents find themselves discussing real-world political issues with their students at the dinner table.

Throughout, students are encouraged (if not downright required) to engage in evidence-based politics, which has the effect of reframing the world around them—often in a context they’d never considered before. “They can’t just pull arguments out of thin air,” quips Snively. “If a candidate has a plan to fix healthcare or raise people out of poverty, they have to explain how they are going to pay for it. Each year, I have to explain that the government can’t hold a fundraiser; a bake sale isn’t a solution for deficit spending.”

Both Snively and Stewart note a fine line between guiding productive discourse and avoiding any influence on their students’ viewpoints. “Most politicians get into politics because they want to help out. It’s important for students to realize that there aren’t simple solutions. There are different ways to get to a goal, and we don’t always have to agree on the path we take,” says Snively. “There’s rarely anything in politics that’s a clear-cut ‘yes and no’ or ‘right and wrong’ issue—when it comes to public discourse, the answer is often somewhere in the middle. And what it comes down to is: how do you judge the merits of different approaches?”

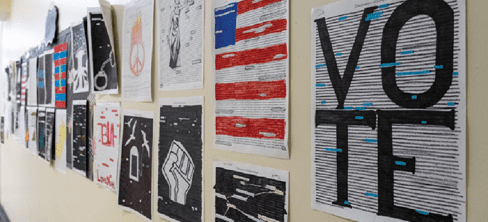

“We want students to be responsible, engaged citizens,” says Stewart. “That’s why we spend time going over real campaign ads from years past and create a public forum to discuss the issues. We are building media literacy and giving them the toolkit to be analytical thinkers.”

“And they’re having fun, in the process,” adds Snively.

Participatory Democracy

Like their Middle School peers—Upper School students study the electoral process each year. However, unlike their younger counterparts, the government mechanisms and politics that they examine are ones in which they will soon participate.

This year, the Center for Community Engagement’s Maggie Grant worked with students to hold a voter registration drive. (In North Carolina, anyone 16 and older can register to vote, although you must be at least 18 to cast a ballot.)

In Maret Jones’s Advanced U.S. Government and Politics course, students learn about the structure and makeup of the government and U.S. political process through discussions of current events. Jones works hard to allow students to explore current political issues that are rarely, if ever, discussed in other classes while encouraging students to respect each other’s opinions. “It’s absolutely critical to create an atmosphere of trust in my class so that they can talk openly about their experiences and feel comfortable formulating their own ideas,” offers Jones. “Putting issues in contexts that feel relevant to their lives helps them grasp those topics and build a dialogue with each other.”

One key aspect of Jones’s class is helping students discern the difference between factual statements and political rhetoric. “I want them to be able to weed their way through stylistic choices and digest what’s really being said. I want them to be savvy consumers of political culture and always remember that words have meaning.”

To better understand how we measure the impact of those words, throughout the fall semester, Jones worked in parallel with Upper School math department chair Craig Lazarski to show students the ins and outs of polling. Students have learned about the statistical theories behind sampling and different ways to model the electorate (likely voters, registered voters, etc.) and consider how polls—and their results—are sometimes used for political effect, such as push polls and voter targeting.

This fall semester, the Community Engagement class, guided by Dr. Michael McElreath, is focused on “Democracy

in North Carolina.” Chosen by students, the topic requires a deep dive into voting and voting rights in the state. Students have examined the history of voting rights, turnout, voter disenfranchisement, gerrymandering, and the intersection of race, economics, and political engagement. Through the course, they’ve met with election attorneys, voting rights activists, and local election officials to examine these issues from a broad range of perspectives. As a result, the class has issued public calls to the Cary Academy community to ensure that everyone who can vote does, no matter their political affiliation.

Finally, recognizing that elections can be stressful and divisive, especially in a year filled with social and economic tensions, the Center for Community Engagement along with Meirav Solomon, CA’s Student Dialogue Leader, partnered with CoEXIST to create a series of structured community dialogues. These created spaces for students to share and support each other as they processed the stresses of the pandemic, racial justice movements, economic strains, and the partisan tensions surrounding the election.

In the wake of Election Day, the Upper School’s conservative and liberal student clubs, as well as a number faculty and staff affinity groups, created safe spaces for students to either take a respite from politics or share their thoughts in a supportive environment following the election results.