I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the value of a good design challenge—one that taps into students’ intrinsic motivation, encourages experimentation and problem-solving and treats failure as an essential part of the path to success.

The wheels started turning for me (literally) at the recent ISEEN Winter Institute in Arizona, where I had the opportunity to step out of the teacher role and experience a design challenge as a learner. The project: to build a rocket car that would be launched at high velocity directly into a wall but allow its passenger, a raw egg, to survive the impact. Judging from the scorch marks on the chassis my partner and I were given to begin the task, there were going to be actual flames shooting out the back of this vehicle. And judging from the yellowish goo dried to the wall that was our target, there were going to be some spectacular fails in this process. I was hooked!

My partner and I took about an hour to design and build our first prototype, and with our aerodynamic egg basket secured to our chassis, we hoped that we had that ideal combination of speed, aim, and cushioning to protect our egg and win the race.

Alas, we did not.

The speed was good, the aim was decent, but poor little Eggbert suffered a serious shell fracture. No yolk splattered on the wall, but still, not the outcome we wanted for our fragile passenger.

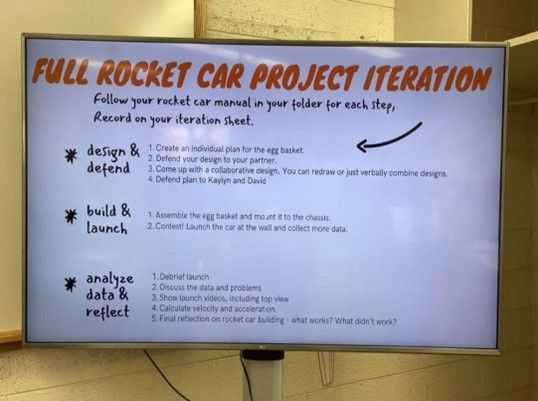

If this had been a one-and-done type project, we might have earned a C+ for the vehicle we created. But because this was framed as a design challenge, we were instead encouraged to reflect upon our results, make changes, and try again. And that’s where the learning process really took off.

My partner and I began our reflection by reviewing a video of our launch, using the hash marks on the ground and the video’s frame rate to calculate our average speed and our acceleration, and from there, we were able to approximate our speed at impact. This led to conversations about air friction, kinetic energy, potential spring energy, and heat. In short, all kinds of concepts from math and physics were coming to life as we considered ways to maintain our speed, improve our aim, and perhaps most importantly, better protect our little albumen friend. Not only was I totally engaged by this activity, but I find that I am still able to recall most of what I learned that day precisely because it was anchored in such a memorable hands-on experience.

A couple of weeks after the rocket car challenge, I came to campus on a Saturday to help out with the USA Young Physicists Tournament. It was a busy weekend at CA, not only for our USAYPT group but also for our Science Olympiad and robotics teams in both Middle and Upper School. Everywhere I looked in the CMS, there were kids building and testing, calculating and troubleshooting, rebuilding, and refining, much the same way I had done in the rocket car challenge. These students could not have been more engaged in what they were doing as they designed to learn.

The USAYPT group spent the day on the NCSU campus, presenting and defending their results in four college-level physics challenges. The biggest surprise for me, though, came not during the tournament itself, but at the end of the day, when I arrived in a Charger bus to transport one of the visiting teams from the tournament venue back to the hotel. As the students boarded the bus for “home,” they were still excitedly talking about the relative merits of the solutions that had been shared and batting around ideas for improvements. I actually had to interrupt them when we pulled up to the hotel to tell them that we had arrived and that it was time to get off the bus. Riding in a vehicle covered with question marks, these students just couldn’t stop iterating, and I couldn’t stop smiling.

Yet another opportunity to observe the magic of a design challenge came my way last Wednesday, when I had a chance to watch some of our 8th-grade science students tackle a problem related to our current supply chain woes–a topic that the students could certainly relate to after the long delay in receiving their new computers. Their challenge: to design a floating storage device (barge) that might help relieve some of the congestion at our ports. The 8th graders built prototypes of their devices from designs they had sketched, and then tested those prototypes in large tubs of water, making design changes as they discovered through a process of trial and error which barge shapes could hold the most weight and what materials would be most buoyant. It was wonderful to hear the language of discovery, innovation, and collaboration in action as the students constructed, tested and refined: “What if we…?” | “Why did it..?” | “How could we…?” | “Do you think…?” | “I wonder…” | “Oops!” | “Let’s try ….” As with the rocket car challenge, the physics tournament, the Science Olympiad projects, and the robots, here, too, the emphasis was on doing, reflecting, and trying again.

I feel lucky to work at a school where teachers embrace design thinking and enthusiastically engage students in all kinds of design challenges, not only in classes but also through extracurricular and X-Day activities. Design challenges reflect our belief that learning is an iterative and interdependent process, and they have become a key ingredient in the mission recipe that makes Cary Academy such an exciting place to learn and grow.