Amaranth greens. Bitter melon. Long beans. Yu choy. Asian chiles. Next year, families across CA will have the opportunity to discover these delicious flavors firsthand—many for the first time—all while learning about and supporting our local Burmese refugee community.

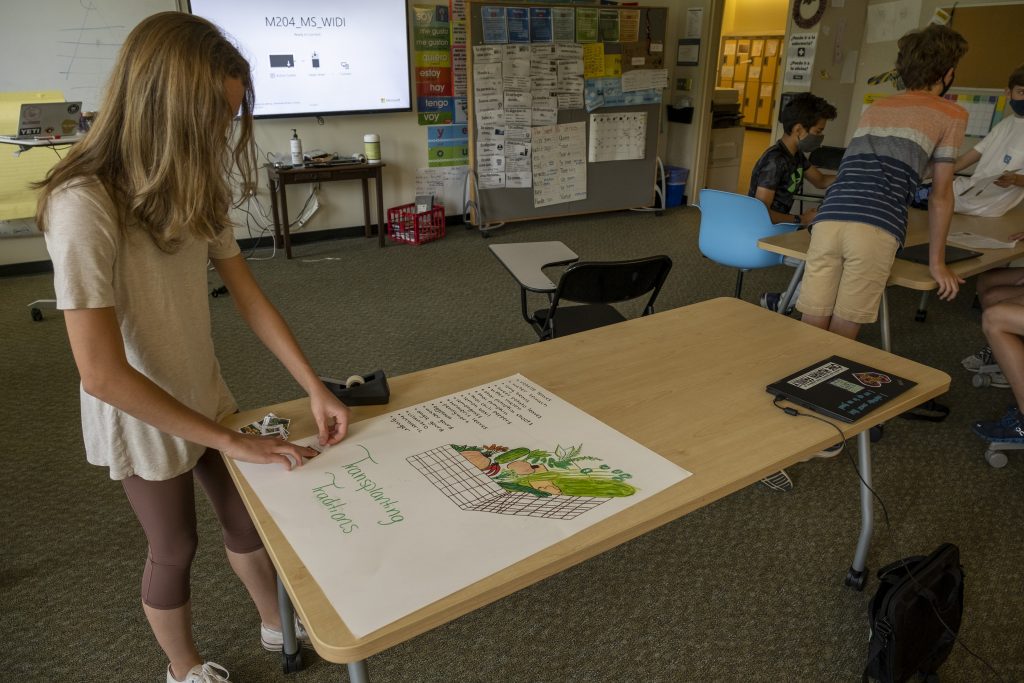

It’s all thanks to a service-learning pilot program led by seventh-grade Migration Collaboration students and faculty in partnership with our Center for Community Engagement and Transplanting Traditions Community Farm, a local nonprofit aimed at uplifting food sovereignty in the Burmese refugee community through access to land, education, and opportunities for refugee farmers.

CA families that subscribe to the CSA will receive a weekly box of organic vegetables locally farmed by Burmese refugee farmers (possibly with an occasional assist from CA students on Flex Days). In each box, a pamphlet thoughtfully researched, designed, and produced by Migration Collaboration students will offer information, not only on the vegetables included, but share profiles of the refugee farmers that produced them, the crisis they faced in Burma, and other ways the CA community can get involved to help.

“The pamphlet comes with the food, so it adds a sense of reality to it. These are actual physical people, these are the actual vegetables they grew, this is what they have been through, and what others like them are still going through,” explains Finn Miller ’26, who helped to create the profiles that appear in the pamphlet. “It’s a quick way to help, to raise awareness and get more people to learn about what they have been through.”

“I think it is cool that people can buy different types of vegetables that are from where some of our local refugee farmers are from,” adds Dana Jhoung ’26, who participated on the student-led communications committee tasked with promoting the initiative to the broader CA community. “These refugees have come a long way to share their culture—and that’s not easy. Transplanting Traditions gives them not only a job and a home, but an important way to share their background and history.”

Digging Deep

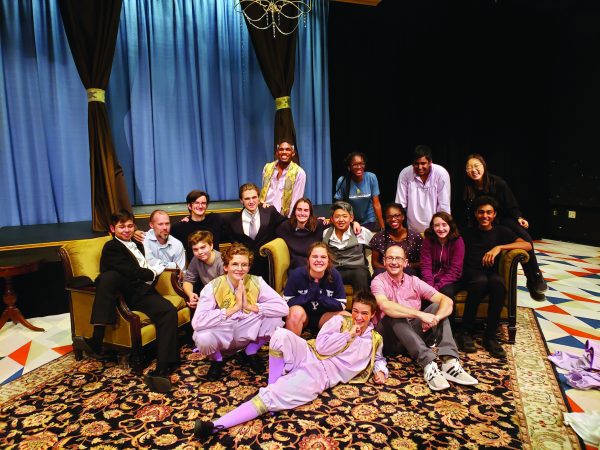

The hands-on service project is an outgrowth of the larger seventh-grade Migration Collaboration project. Now entering its third year, Migration Collaboration—led by seventh-grade social studies teachers Lucy Dawson and Matt Koerner, in partnership with Service Learning Director Maggie Grant—is an immersive, interdisciplinary, and experiential exploration of human migration. It offers students a deeper understanding of the refugee experience through personal interactions with refugees and members of local refugee-serving organizations; explorations of non-fictional and fictional migrant and refugee narratives; interdisciplinary, student-led research projects; and various hands-on excursions where students work side-by-side with refugees and community partners.

“It’s been an amazing project,” enthuses Daphne DiFrancesco ’26, who participated in Migration Collaboration and the Transplanting Traditions service-learning project this past year. “I’ve learned so much about different communities and migration in general. I’ve done different research projects on stuff like this before, but it’s usually just reading website after website or the occasional book. With this, I was able to take a deep dive and connect with the community and really interact. It made me realize how we’re all connected. The experiential piece just adds so much.”

As president of the Student Leadership Club, next year, Difrancesco hopes to take what she learned to determine constructive ways that CA students might support North Korean refugees. “There are only a handful of organizations that work with North Korean refugees because it is so dangerous to do so,” she explains. “I’m hoping to partner up with these organizations to see how we might help with fundraising.”

A rich harvest

And that, of course, is precisely the goal: To help students develop the empathy, connections, and competencies needed to lead ethical and equitable community activism—all while gaining a more nuanced understanding of the complex historical, social, cultural, economic, and political forces that shape human migration.

“We want to inspire our students to understand not only why people move, but how we can responsibly support those that do,” explains Koerner. “How we can help them in our own community.”

Central to that effort is challenging racist and reductive stereotypes of the immigrant refugee. “We want students to understand that refugees don’t look one way—there isn’t a certain race or ethnicity or class or level of education,” adds Dawson. “It isn’t a monolith; there isn’t a singular refugee experience.”

That empathy-building process starts with getting students into the community where they can build authentic, personal connections that disrupt stereotypes, broaden perspectives, and allow students to put themselves in someone else’s shoes. That’s where the Center for Community Engagement comes in, building partnerships within the broader Triangle-area community that facilitate impactful, memorable, and long-lasting connections and experiences for students that put a human, relatable face on the abstract concept of migration.

Take, for instance, one of Dawson’s favorite moments: when Scott Philips, the North Carolina field representative at the United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCRI), brought two of his nearly-arrived clients—Israel and Mordecai—to meet with students. The two Congolese teenagers shared their experience of growing up in a Ugandan refugee camp, having never lived in the country of their birth. It was a wildly different experience than that of most CA students, and yet, through conversation, they found common ground.

“Our students got to hear about our guests’ experiences—about their culture, about growing up in a camp—firsthand. It was just such a cool exchange,” recalls Dawson with a smile. “Our kids were just in awe. They were asking questions like ‘What’s math like there?’ and were dumbstruck when our guests said it was ‘way harder’ than it is here at CA. They were connecting as humans, as kids, bonding over the Black Panther movie and candy preferences. It was such an authentic exchange, and one that upended preconceived stereotypes.”

Koerner’s favorite moment? When Pauline Hovey, a volunteer with Annunciation House—a nonprofit in El Paso, Texas that offers hospitality to newly arrived migrants, immigrants, and refugees at the border—visited, sharing stories from specific families that were undergoing the asylum-seeking process.

“She was able to share specific stories and faces, to paint a vivid picture of what this family, this woman, this child went through. It made it very real for students—they could connect,” offers Koerner. “And, she was working only with the people that had actually gained asylum status. Just the sheer numbers of even that population—which is less than 1% of the actual people that arrive at the border—it was mind-blowing for our students. I had so many students come up to me and ask to get involved after her presentation.”

And, of course, that’s the point.

“Making those connections, hearing the personal stories, the challenges of those that have had to resettle, it deepens empathy—both for our students and for the educators involved in this project. You can see the light bulbs turning on.” says Grant.

Miller—whose research project focused on unaccompanied minor migration—is one of the students who experienced one of those light bulb moments. “I realized that, here in our little bubble in Raleigh, we’re all pretty privileged and live good lives, but there are so many scary things happening in the world, so many people and things that need our help. We need to do whatever we can to publicize it, to make people care, to help.”

Cultivating Community

Once those light bulbs are turned on, Migration Collaboration aims to empower and equip students with the critical insights and skills needed to lead impactful change in their own backyards—and to do so in a way that stresses partnership and equity. Indeed, while fostering student empowerment is central to the project, so too is cultivating savvy leadership and collaborative skills. And that includes knowing when to sit back and listen and when to lead, or when to adjust an idea or let go of it altogether if it doesn’t have community buy-in or address community needs (no matter how invested you may be personally).

Dawson, Grant, and Koerner are hopeful that next year’s cohort of Migration Collaboration students will be putting those collaborative skills to action. In the long-awaited next stage of the project (postponed this year due to COVID), students will propose and develop their own service initiatives designed in partnership with community stakeholders.

“It’s a balancing act,” offers Grant. “We want these to be student-directed projects and ones that empower students in their learning, but they must learn to do so responsibly. First and foremost, they must listen to the community. That’s why we stress empathy, listening, and interviewing. What are the people in our community telling us that they are experiencing, that they need? Is there a way—because sometimes there isn’t—that we can be a part of a solution? How can we utilize our resources—our time, energy, money, whatever—to meet that need in partnership with the community.”

Cultivating respect for local expertise, for the deep knowledge that partners can bring to the table—even those not traditionally viewed as educators—is crucial. “We’re mindful about using the term ‘expert,’” explains Grant. “We use it not only when we are going into the community to learn directly from professionals who are working with immigration policy or programs, but when referring to refugee newcomers themselves. It is important that our students understand and respect the kind of expertise that comes from personal experience.”

“The title we chose for this project—Migration Collaboration—was quite purposeful,” reflects Koerner. “It’s not just about our students collaborating in the classroom on projects—it is about working together in partnership with the broader community. We wanted to set that tone, to be clear about our intentions from the outset. We’re not saving anyone—our community is broad and diverse. We are all in this together.” He smiles, “I can’t wait to see what our students and their partners will do next.