With the cancellations of long-planned anticipated travel, summer camps, and social gatherings looming large, a COVID-tainted summer was a far cry from what most had imagined in the early days of 2020. Rather than focus on what was lost, however, an enterprising group of Cary Academy Speech and Debate students instead saw an opportunity.

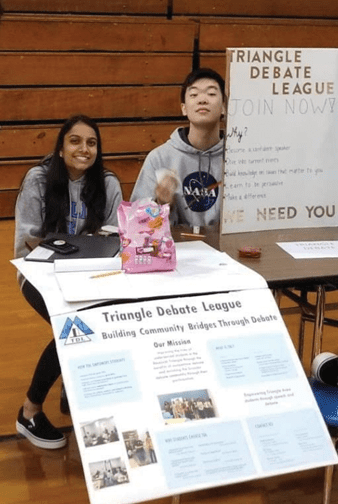

The students are proud volunteers with the Triangle Debate League (TDL). Thanks to their vision, leadership, and innovation, over 80 local youths that would not otherwise have access to speech and debate programming were able to participate in a world-class summer camp experience virtually.

TRIANGLE DEBATE LEAGUE

Founded at Cary Academy and now in

its third year, TDL is a local collaborative nonprofit inspired by the work of the national organization, the Urban Debate League. Dedicated to broadening the debate community—long a domain of privilege—it aims to extend competitive speech and debate to public schools that do not have the staff or funds to support the activity.

“Speech and debate offers so many rich benefits: improved critical thinking, advocacy, public speaking skills, even heightened self-esteem and civic engagement,” offers Shawn Nix, Co-Director of CA’s Speech and Debate program. “Unfortunately, though, it is also an activity that requires a lot of resources—faculty, transportation, extensive travel,

and expensive entry fees. It is often cost-prohibitive to resource-strapped institutions.”

That’s where TDL comes in. A collaboration between student-coaches from the University of North Carolina and Duke University, as well as CA faculty, students, and alums, TDL works with local, partner public schools to deliver debate programming.

CA students involved with TDL volunteer as peer-mentors—sharing their knowledge, helping with research, serving as judges, offering critique, and facilitating group activities with TDL peer participants. Several CA alums have also pitched in, helping to run tournaments and serving as debate coaches. To date, they have helped to bring Congressional Debate to four public high schools in Durham, North Carolina.

GOING VIRTUAL

TDL volunteer and captain of public forum debate for CA’s Speech and Debate team, Aryan Nair (’22), was the initial mastermind behind the idea of a virtual summer camp: “I had worked on Triangle Debate League’s summer camp the year prior and had been looking forward to doing it again,” Nair explains. “With COVID, I realized that an in-person camp wouldn’t be feasible, so I approached Mrs. Nix about doing a virtual one.”

With encouragement from his CA teachers, Nair got to work enlisting the help of other students to form an initial curriculum planning committee. Together, they began to meet biweekly to sketch out what a successful virtual camp might look like.

Ultimately, they settled on a week-long format, with each day designed around a specific aspect of speech and debate. The week would culminate in a tournament where campers could put it all together to show off their newly acquired rhetorical skills.

Plan in hand, they recruited additional CA peers to help bring the ambitious vision to fruition. Subcommittees were formed, and tasks delegated to address the camp’s multifaceted needs—from communications and customer service, to technology and web development, to coaching and instructional support.

Not unlike their CA teachers, camp leaders grappled with the challenge of transitioning an in-person experience to a successful virtual one—of creating an engaging experience that would retain the interest

of a Zoomed-in (and, at this point in the pandemic, Zoomed-out) digital audience.

“We wanted to give the camp a really good structure. We knew we didn’t want to just give lectures via Zoom,” explains Nair. “A

lot of people tend to zone out in the virtual environment; it isn’t always the most engaging.”

To make the most of both their audience’s attention spans and limited time together, they landed on offering a blend of synchronous and asynchronous content and experiences.

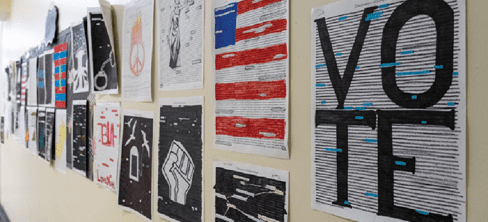

Campers received carefully planned asynchronous instruction through pre-recorded video segments that were devised, scripted, recorded, and edited by members of the curriculum committee. Topics ranged from sound research methodologies to

chamber etiquette, to the art of public speaking and persuasion, to speech writing and the ins and outs of crafting a compelling argument, to rebuttal and cross-fire techniques, and many others in-between.

“A lot of us had been to debate camp ourselves, or had volunteered at other debate camps, so we already had some resources that we had used or created before. We started pooling those resources, turning them into video presentations to make them more accessible,” explains Nair.

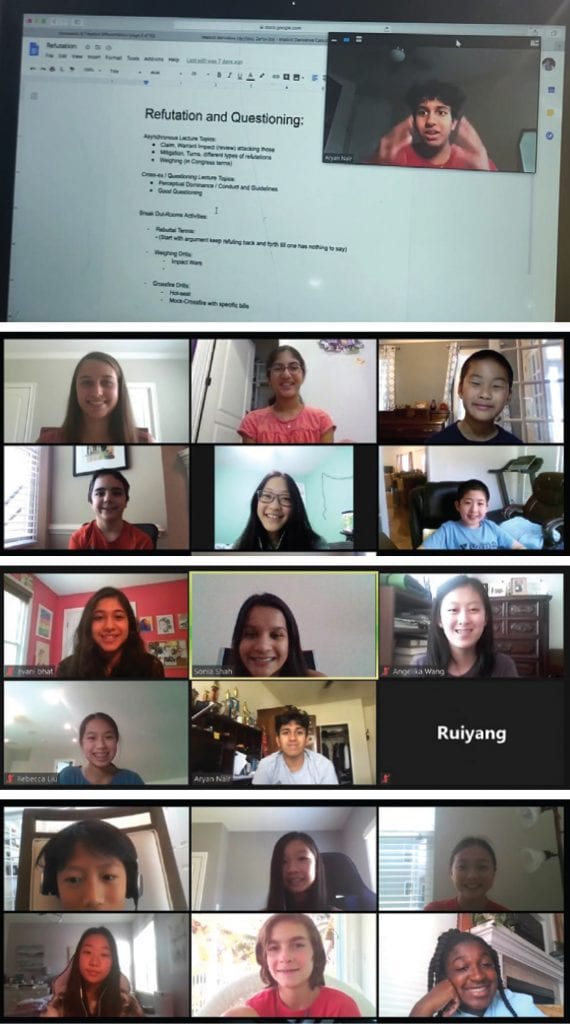

Complementing the video instruction, the coaching and instruction committee stepped in to devise and run in-person online synchronous drills via Zoom that allowed campers to put their new skills to work in small groups. It also offered campers important face time with coaches, who answered questions and gave tips on impromptu topics, like strategies to overcome stuttering or repetition.

A technology committee tackled arguably one of the most crucial components: establishing the virtual platform that would form the digital backbone of the camp.

Ritvik Nalamothu (’21), who led that effort, explains: “TDL had an existing website, but it was just a supplementary resource to our in-person operations. For camp, we had to convert it to be the primary resource; we had to develop a comprehensive virtual platform.”

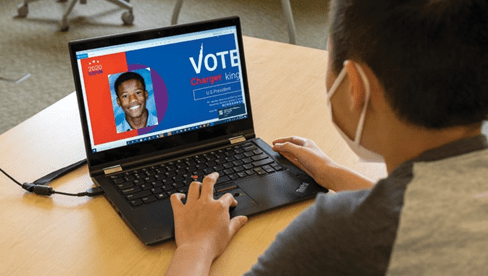

And they did just that, designing and building an impressive one-stop virtual experience where campers could access all the resources they needed—welcome videos, daily and weekly schedules, links to assigned Zoom rooms, and a digital library of the video learning resources that had been created.

Nalamothu also worked closely with RJ Pellicciotta, CA’s Co-Director of Speech and Debate, and debate teacher Shannon Nix, to get camp tournaments up and running on the National Speech and Debate Association’s official Tabroom.com competitive platform. Doing so ensured that campers would have an authentic experience, one that reflected the look and feel of a typical tournament they might attend in their competitive future.

BEYOND EXPECTATIONS

In all, the camp represented a highly concerted and collaborative team effort.

“There were a lot of students contributing across a wide variety of roles,†reflects Nalamothu. “We had students participating with me on the tech team, over a dozen others creating the curriculum. We had students that were counselors. Others worked communications or served as judges.

“It was remarkable to see the amount of student capital that went into it—and to see how their individual contributions came together in the successful final product.”

Impressed by the planning, infrastructure, and resources developed by the students, Nix lobbied them to expand the camp’s planned capacity and open the experience to CA’s Middle School students. The leaders agreed, and within 24 hours, registration jumped from 35 to 82 participants.

Far from flustered, the camp leaders took it in stride, pivoting to offer both morning and afternoon sessions, one for middle and another for high school students.

Speech and debate teachers Shawn and Shannon Nix were blown away by remarkable leadership and initiative exhibited by their CA students. “I’m continually amazed by them,” marvels Shawn. “Honestly, I don’t know how they did it all. They ran with it, and it went off without a hitch.”

By all accounts, the camp was an unequivocal success. Comments provided on campers’ feedback surveys (yep, the students planned for feedback to improve future experiences) were unanimously positive. “I haven’t had my brain working like this since lockdown—thanks for making me able to think again,” shared one camper.

Parents and campers alike exalted the camp as a positive and fun learning experience, expressing deep gratitude for camp leaders. Others were enthused over their new-found excitement to further explore speech and debate (enthusiasm that yielded real-world results, this fall, with the creation of the first-ever Middle School Debate Club).

For their part, camp leaders are proud of their efforts. And they are hopeful

that the virtual pivot necessitated by COVID will become a mainstay in the debate community—even after the pandemic is over.

“TDL has opened the pathway for expanding access to speech and debate resources. And in many ways, COVID is democratizing speech and debate,” reflect Nalamothu. “The shift to virtual venues, the removal of logistical obstacles like transportation, means that more people will have access, that TDL students will be able to participate in the same tournaments

CA students do.”

A TWO-WAY STREET

Nix is always quick to point out that the learning in Triangle Debate League goes both ways—that CA’s student volunteers benefit as much from the experience and their fellow TDL participants as the participants do from them. By all accounts, the camp was no different.

“Over the course of doing Congressional debate throughout high school, I have developed skills to synthesize information and present it persuasively in ways that allow me to advocate for things that I believe in,” offers Nalamothu. “It was immensely rewarding and gratifying to see the same progress that I have made, in others, with just a week at camp—to watch as our students went from having rudimentary skills to being able to deliver well-researched, persuasive speeches on a wide variety of topics.”

Running the TDL camp was as much a learning experience for us as our campers,” reflects Nair. Whether it was honing their own debate skills or teaching, or working on a website, or learning how to lead and organize a project of this magnitude—everyone took away important skills that they can use in their future.”

For Jane Sihm (’22), who helped with camp communications and moderated tournaments, the lessons were both practical and philosophical. “I learned so much: communication skills, collaboration, leadership. But my biggest takeaway was not to let barriers stop you from achieving your goals,” she muses.

“There were a lot of obstacles to pulling this off in a pandemic, but we didn’t let that stop us. We shifted our mindset; we broke it down into manageable pieces. And, before we knew it, we had helped dozens of kids. We had made a difference.”